…And Need Before Your Next Quarantine

Pew Catherine lacey

This 2020 publication quietly slipped in and took a seat on the back row. Perhaps it has gone unnoticed because at barely more than 200 pages, and dressed up to look like a prayer book, it has literally been lost among the other books on the case. That’s too bad, because this little book has a lot to say.

The premise of the novel is how a small Southern town reacts when finding a homeless, gender-neutral person of uncertain ethnicity asleep on a church pew on Sunday morning. As various households extend hospitality to “Pew,” who also appears to be mute, confidences are shared that begin unraveling the town’s history. And oh, the hypocrisy (bless their hearts)! Packed with social and moral dilemmas, this novel provides plenty of fodder for discussion at your next Book Club.

There, There Tommy orange

Tommy Orange is angry. Really angry. He’s angry about the plight of contemporary American Indians, and he wants everyone to read about it. He wants us to understand what it’s like to be caught between two worlds: one that you’re trying to preserve and another that doesn’t seem to want you.

And no, this is not an episode of Yellowstone. This is Tommy Orange’s debut novel, and besides bringing a meaningful perspective to the struggles of modern urban American Indians, it’s just plain good literature. He knocks it out of the park on his first try. Wow.

Mr. Orange speaks through twelve different characters, a strategy that is difficult to pull off but is impressively well-executed in this novel. Each character propels the main plot line while adding a different dimension to the saga. The end result is a perfectly-seasoned portrait that will stay with you long after you’ve finished the book.

florence adler swims forever rachel beanland

Rachel Beanland gives us another solid debut novel that didn’t quite get the recognition it deserves. It’s about a family who keeps the death of a daughter secret to protect her pregnant sister. I’ll admit I found that plot line a bit dubious at first. Then I read in the author’s note that the story is actually based on real events from her own family (so file that under “truth is stranger than fiction”).

The Adler family is Jewish, and the patriarch, Joseph, left family behind in Europe when he emigrated to America. It is now 1934, and in a secondary plot line, Joseph is feeling pressure to help a “family friend” escape Nazi Germany without revealing the true nature of her relationship to him. The novel’s impact is in demonstrating how family secrets can undermine relations between family members, even when intentions are pure.

As an added bonus, it paints a picture of the early boom years of Atlantic City, back when the town was, well, charming.

Prince of tides Pat conroy

Oh, I know — Prince of Tides is old news and was even made into a movie starring none other than Babs herself. But after everyone went gaga over Where the Crawdads Sing, I began to wonder if anyone remembered it anymore.

I’ll admit, Delia Owens, a nature writer, did an impressive job with her descriptive writing about the Outer Banks. But Conroy, a Southerner, writes about life on the South Carolina coast with real authenticity (and without the distraction of poorly-executed accents). You won’t find a backwoods loner in this story; but see, when backwoods parents stick around they can create lots more trouble, which in turn makes for a much more complex story line. One that only a New York City psychiatrist can untangle.

Regardless of how you feel about the Crawdads, don’t miss the Tides. It’s equal parts painful and beautiful in a way you won’t forget.

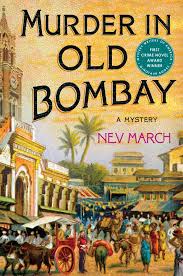

Nev March’s novel debuts with an award from the Mystery Writers of America in its wake, so snatching up an advance copy was not a difficult choice. The book lives up to its early praise, delivering intrigue enfolded in a complex and volatile political environment. The main characters are developed well as the novel progresses, and left me hoping to see them again in later publications.

Nev March’s novel debuts with an award from the Mystery Writers of America in its wake, so snatching up an advance copy was not a difficult choice. The book lives up to its early praise, delivering intrigue enfolded in a complex and volatile political environment. The main characters are developed well as the novel progresses, and left me hoping to see them again in later publications.